HISTORIC INNS OF SOUTHWARK. 1868

The Borough High street 1817 directory plus

Useful street listing : Borough High street, Southwark 1842 directory

Brilliant reference : 1746 , 1868 & Google

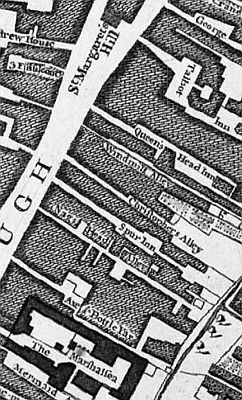

Borough High street - in 1746

The borough of Southwark, more especially the High-street, was for many ages the only entrance into London from Kent, Surrey, and Sussex, and the chief road to and from France, and the shrine of St. Thomas à Becket at Canterbury. Thither, in times before the Reformation, pilgrims resorted by thousands every year: hence it is not surprising that Southwark became celebrated for its inns, which, from the accommodation they afforded to travellers, brought no inconsiderable profit to the inhabitants of this part of the metropolis.Stow, in his Survey (first published in 1598), says: “From thence (the Marshalsea) towards London Bridge,

VOL. I.

on the same side, be many fair inns for receipt of travellers, by these signs: the Spurre, Christopher, Bull, Queen's Head, Tabard, George, Hart, King's Head, &c.” Of these inns mentioned by the old chronicler, the Spurre, the Queen's Head, the Tabard (Talbot), the George, and the King's Head still exist as inns for travellers. The Tabard (or Talbot) is the most celebrated of these hostelries, and is renowned in Chaucer's verse as the place where he and the nine-and-twenty pilgrims met, and agreed to enliven their pilgrimage to the shrine of St. Thomas à Becket at Canterbury by reciting tales to shorten the way. The date of the Canterbury Pilgrimage is generally supposed to have been the year 1383; and Chaucer, after describing the season of spring, says: “Befelle, that in that seson, on a day, In Southwerk, at the Tabard as I lay, Redy to wenden on my pilgrimage To Canterbury, with devoute corage, At night was come into that hostelrie Well nine-and-twenty in a compagnie Of sondry folk, by aventure yfalle In felawship; and pilgrimes were they alle, That toward Canterbury wolden ride. The chambres and the stables weren wide, And wel we weren esed atte beste, And shortly, whan the sonne was gon to reste, So hadde I spoken with hem everich on That I was of hir felawship anon,

And made forword erly for to rise, o

To take oure way ther as I you devise.”

The Tabard is again mentioned in the following lines:

“In Southwerk at this gentil hostelrie, That highte the Tabard, faste by the Belle.”

Henry Bailly, the host of the Tabard, was not improbably a descendant of Henry Fitz Martin, of the borough of Southwark, to whom King Henry III., by letters-patent dated 30th September in the fiftieth year of his reign, at the instance of William de la Zouch, granted the customs of the town of Southwark during the king's pleasure, he paying to the exchequer the annual fee-farm rent of 10l. for the same.

By that grant Henry Fitz Martin was constituted bailiff of Southwark, and he would thereby acquire the name of Henry the Bailiff, or le Bailly.

But be this as it may, it is a fact, on record, that Henry Bailly, the hosteller of the Tabard, was one of the burgesses who represented the borough of Southwark in the parliament held at Westminster in the 50th Edward III., A.D. 1376; and he was again returned to the parliament held at Gloucester in the 2d Richard II., A.D. 1378.

We cannot read Chaucer's description of the host without acknowledging the likelihood of his being a popular man among his fellow-townsmen, and one likely to be selected for his fitness to represent them in parliament. His identity is further corroborated by the following extract from the Subsidy Roll of 4th Richard II., 1380, dorso,

"Henr' Bayliff, Oystyler, Xrian, Ux'.eius....ijs"

from which record it appears that Henry Bayliff hosteller, and Christian his wife, were assessed to the subsidy at two shillings. After the dissolution of the monasteries, the Tabard and the Abbot's House were sold by King Henry VIII. to John Master and Thomas Master; and the particulars for the grant in the Augmentation Office afford descriptions of the hostelry called the Tabard, parcels of the possessions of the Monastery of Hyde, and the Abbot's Place, with the stable and garden belonging thereto. The Tabard is mentioned to have been late in the occupation of one Robert Patty; but the Abbot’s Place, with the garden and stable, were reserved to the late Bishop Commendator, John Saltcote, alias Capon, who had been the last abbot of Hyde, and who surrendered it to King Henry VIII.; and after being made Bishop of Bangor, in commendam with the Abbey of Hyde, subsequent to the surrender of the abbey, he was preferred to the see of Salisbury, in 1539, which he retained till his death in 1557.

As regards the name of the inn, Stow says of the Tabard, “that it was so called of a jacket or sleeveless coat, whole before, open on both sides, with a square collar, winged at the shoulders: a stately garment of old time, commonly worn of noblemen and others, both at home and abroad in the wars; but then (to wit, in the wars) their arms embroidered or otherwise depicted upon them, that every man, by his coat of arms, might be known from others. But now these tabards are only worn by the heralds, and be called their coats of arms in service.”

From Speght we learn that the original Tabard was standing in 1602. It was an ancient timber house, probably as old as Chaucer's time, and there is a view of it in Urry's edition of Chaucer.

On the brestsummer-beam of the gateway facing the street was formerly inscribed, “This is the inne where Sir Jeffry Chaucer and the nine-and-twenty pilgrims lay in their journey to Canterbury, anno 1383.” This was painted out in 1831 : it was originally inscribed upon a beam across the road, whence swung the sign, removed in 1763. The sign was changed about 1676, when, says Aubrey, “the ignorant landlord or tenant, instead of the ancient sign of the Tabard, put up the Talbot, or dog!”

The last of the oldest buildings was of the age of Elizabeth; and the most interesting portion a stone-coloured wooden gallery, in front of which was a picture of the Canterbury Pilgrimage, said to have been painted by Blake; immediately behind was the Pilgrims' Room of tradition, but only a portion of the ancient hall. The gallery formerly extended throughout the inn-buildings. The inn facing the street was burnt in the great fire of Southwark, 1676.

Mr. Corner, F.S.A., who has left the best account of the Southwark inns, having personally examined the premises at some risk, came to the conclusion that the oldest existing remains were not earlier than 1676: the whole has been removed.

The George inn is mentioned by Stow, and even earlier, in 1554, the 35th year of King Henry VIII. Its name was then the St. George. There is no further trace of it till the seventeenth century, when there are two tokens issued from this inn. Mr. Burn quotes the following lines from the Musarum Delicioe, upon a surfeit by drinking bad sack at the George tavern in Southwark:

“O, would I might turn poet for an hour,

To satirise with a vindictive power

Against the drawer, or could I desire

Old Johnson's head had scalded in the fire;

How would he rage, and bring Apollo down

To scold with Bacchus, and depose the clown

For his ill government, and so confute

Our poets, apes, that do so much impute

Unto the grape inspirement.”

In the year 1670 this inn was in great part burnt down and demolished by a fire which happened in the Borough, and it was totally burnt down by the great fire in Southwark, in 1676: the owner was at that time John Sayer, and the tenant Mark Weyland. Of this great Southwark fire it may be interesting to note that it took place ten years after the Great Fire of London: it burnt a great part of Southwark, from the bridge to St. Margaret's Hill, including the townhall, which had been established in 1540, in the Church of St. Margaret. The buildings being as yet, like old London, chiefly of timber, lath, and plaster, the fire spread extensively. It broke out on May 27th, about four in the morning, and continued with much violence all that day and part of the night following, notwithstanding all the care and endeavours that were used by his Grace the Duke of Monmouth, the Earl of Craven, and the Lord Mayor, to quench the same, as well by blowing up of houses as other ways; his Majesty, accompanied by the Duke of York, “in a tender sense of the calamity, being pleased himself to go down to the bridge in his barge, to give such orders as his Majesty found fit for putting a stop to it, which, through the mercy of God, was finally effected, after that about 600 houses had been burnt or blown up.”

The following is from the diary of the Rev. John Ward, written a few years later:

“Grover and his Irish ruffians burnt Southwark, and had 1000 pounds for their pains, said the Narrative of Bedloe. Gifford, a Jesuit, had the management of the fire. The 26th of May 1676 was the dismal fire of Southwark. The fire begunne att one Mr. Welsh, an oilman, near St. Margaret's Hill, betwixt the George and Talbot innes, as Bedloe in his Narration relates” (Diary of the Rev. John Ward, 8vo, 1839, p. 155).

The fire was stopped by the substantial building of St. Thomas's Hospital, then recently erected.

The present George, although built only in the seventeenth century, seems to have been rebuilt on the old plan, having open wooden galleries leading to the chambers on each side of the inn-yard. After the fire, the host Mark Weyland was succeeded by his widow, Mary Weyland; and she by William Golding, who was followed by Thomas Green, whose niece, Mrs. Frances Scholefield, and her then husband, became landlord and landlady in 1809; Mrs. Scholefield died at a great age in 1859. The property has been purchased by Guy’s Hospital. The George is mentioned in the records relating to the Tabard, to which it adjoins, in the reign of King Henry VIII. as the St. George inn. Two tokens of the seventeenth century, in the Beaufoy Collection at Guildhall Library, admirably catalogued and annotated by Mr. Burn, give the names of two landlords of the George at that period, viz. Anthony Blake, tapster, and James Gunter.

The White Hart is one of the inns mentioned by Stow; but it possesses a still earlier celebrity, having been the head-quarters of Jack Cade and his rebel rout during their brief possession of London in the year 1450, when Henry VI. was king. Shakspeare, in the Second Part of King Henry VI. makes a messenger enter in haste, and announce to the king:

“The rebels are in Southwark. Fly, my lord !

Jack Cade proclaims himself Lord Mortimer,

Descended from the Duke of Clarence house,

And calls your grace usurper openly,

And Vows to crown himself in Westminster.”

And again, another messenger enters, and says:

“Jack Cade hath gotten London Bridge;

The citizens fly and forsake their houses.”

Jack Cade afterwards thus addresses his followers:

“And you, base peasants, do ye believe him? Will you needs be hanged with your pardons about your necks? Hath my sword therefore broke through London gates, that ye should leave me at the White Hart in Southwark?”

Cade entered London from Blackheath, through the Borough, and towards evening he retired to the White Hart, in Southwark. He continued there for some days, entering the City in the morning, and returning at night; but at last, his followers committing some riot in the City, they had the gate shut against them; and ultimately the great body of Cade's followers deserted him, and he fled into Kent, where he was soon afterwards slain at Hothfield.

Fabyan has this entry: “On July 1, 1450, Jack Cade arrived in Southwark, where he lodged at the Hart; for he might not be suffered to enter the Citie.”

The Chronicle of the Grey Friars records this deed of violence committed by Cade and his followers at this place: “At the Whyt Harte in Southwarke, one Hawaydyne, of Sent Martyns, was beheddyd.”

The White Hart lately taken down was not the same building that afforded quarters to Jack Cade; for in 1669 the back part of the old inn was accidentally burnt down, and the inn was wholly destroyed by the great fire which happened in Southwark in 1676. The records of the Court of Judicature inform us that John Collett, Esq., was then the owner of the property, and Robert Taynton, executor of . . . . . was the tenant.

It appears, however, to have been rebuilt upon the model of the older edifice, and realised the descriptions which we read of the ancient inns, consisting of one or more open courts or yards, surrounded with open galleries, and which were frequently used as temporary theatres for acting plays and dramatic performances in the olden time. The reader will, we daresay, recollect Mr. Dickens's admirable description of the White Hart in the Pickwick Papers.

The Boar's Head was the property of Sir John Fastolf, of Caistor, in Norfolk, and who died in 1640, possessed, among other estates in Southwark, of one messuage in the parish of St. Mary Magdalen (now part of St. Saviour's) called the Boar's Head. Mr. Chalmers, in his history of Oxford, says, “It is ascertained that the Boar's Head, in Southwark (then divided into tenements), and Caldecott Manor, in Suffolk, were part of the benefactions of Sir John Fastolf, Knt., to Magdalen College, Oxford.” Henry Windesone, in a letter to John Paston, dated August 1459, says, “An it please you to remember my master (Sir John Fastolf) at your best leisure, whether his old promise shall stand as touching my preferring to the Boar's Head in Southwark. Sir, I would have been at another place, and of my master's own motion he said that I should set up in the Boar’s Head.” This inn was situate on the east side of the High-street, and north of St. Thomas’s Hospital, opposite St. Saviour's Church. In the churchwardens’ account for St. Olave's, Southwark, in 1614 and 1615, the house is thus mentioned: “Received of John Barlowe, that dwelleth at ye Boar's Head in Southwark, for suffering the encroachment at the corner of the wall in ye Flemish Church-yard for one yeare, iiijs.”

There is in existence a rare small brass token of the Boar's Head: in the centre of the obverse is a boar's head (lemon in mouth), and around it, “AT THE BORE’s HEAD;” on the reverse, “IN SOUTHWARK, 1649;” in the field, “B WM..” There is a similar token in the Beaufoy Collection at Guildhall.

At the instance of his friend, William Waynfleet, Bishop of Winchester, Sir John Fastolf gave large possessions in Southwark and elsewhere towards the foundation of Magdalen College. In the Reliquiae Hearnianoe, edited by Dr. Bliss, is the following entry relative to the bequest of the Boar's Head:

“1721. June 2.—The reason why they cannot give so good an account of the benefaction of Sir John Fastolf to Magd. Coll. is, because he gave it to the founder, and left it to his management, so that 'tis suppos'd 'twas swallow’d up in his own estate that he settled upon the college. However, the college knows this, that the Boar's Head, in Southwark, which was then an inn, and still retains the name, tho' divided into several tenements (which brings the college 150l. per annum), was part of Sir John's gift.”

The property above mentioned was, for many years, leased to the father of the author of the present work, and was by him principally sub-let to weekly tenants. The premises were named “Boar's Head-court,” and consisted of two rows of tenements vis-à-vis, and two houses at the east end, with a gallery outside the first floors: the tenements were fronted with strong weatherboard, and the balusters of the staircases were of great age. The court entrance was between the houses Nos. 25 and 26, east side of High-street, and that number of houses from old London Bridge; and beneath the whole extent of the court was a finely-vaulted cellar, doubtless the wine-cellar of the Boar's Head. The property was cleared away in making the approach to the new London Bridge; and on this site was subsequently built part of the new front of St. Thomas's Hospital.

The Bear at the Bridge-foot was a noted house during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and it remained until the houses on the old Bridge were pulled down, in or about the year 1760. This house was situate in the parish of St. Olave, on the west side of High-street, between Pepper-alley and the foot of London Bridge. It is mentioned in a deed of conveyance (dated Dec. 12, 1554, in the first and second year of Philip and Mary); and in the parish books of the same date there is still earlier mention of this house, for amongst the entries of the disbursements of Sir John Howard, in his steward's accounts, are recorded: “March 6th, 1463-4. Item, payd for the red wyn at the Bere in Southewerke, iiid.” And again, “March 14th (same year). Item, payd at dinner at the Bere in Southewerke, in Costys, iiis. iiid. Item, that my mastyr lost at shotynge, xxd.”

Cornelius Cooke, mentioned in the parish accounts of St. Olave's as overseer of the land side as early as 1630, became a soldier, and ultimately was made captain of the Trained Bands. He rose to the rank of colonel in Cromwell’s time, and was appointed one of the commissioners for the sale of the king's lands. After the Restoration, he settled down as landlord of this inn. Gerrard, in a letter to Lord Strafford, dated January 1633, intimates that all back doors to taverns on the Thames were commanded to be shut up, excepting only the Bear at the Bridge-foot, exempted by reason of the passage to Greenwich. The “Cavaliers' Ballad” on the magnificent funeral honours rendered to Admiral Dean (killed June 2, 1653) has the following allusion:

“From Greenwich towards the Bear at Bridge-foot

He was wafted with wind that had water to't;

But I think they brought the devil to boot,

Which nobody can deny.”

There is also another allusion in the following lines from a ballad, “On banishing the Ladies out of Town:”

“Farewell Bridge-foot and Bear thereby,

And those bald pates that stand so high;

We wish it from our very souls

That other heads were on those poles.”

The Bear at London Bridge foot is twice mentioned by Pepys in his Diary: “24th Feb. 1666-7. Going through bridge by water, my waterman told me how the mistress of the Beare tavern, at the Bridge-foot, did lately fling herself into the Thames, and drown herself; which did trouble me the more, when they tell me it was she that did live at the White Horse tavern in Lumbard-street, which was a most beautiful woman, as most I have seen. It seems she hath had long melancholy upon her, and hath endeavoured to make away with herself often.

“3 April 1667. Here I hear how the king is not so well pleased of this marriage between the Duke of Richmond and Mrs. Stewart as is talked; and that he by a wile did fetch her to the Beare, at the Bridge-foot, where a coach was ready, and they are stole away into Kent, without the king's leave; and that the king hath said he will never see her more: but people do think that it is only a trick.”

There is yet another poetical reference to the Bear at Bridge-foot, in a scarce poem entitled The last Search after Claret in Southwark, or a Visitation of the Vintners in the Mint, with the Debates of a Committee of that Profession, thither fled to avoid the cruel Persecution of their unmerciful Creditors. A poem. London: printed for E. Hawkins, 1691, 4to, in which the Bear is thus mentioned (after landing at Pepper-alley):

“Through stinks of all sorts, both the simple and compound,

Which through narrow alleys our senses do confound,

We came to the Bear, which we soon understood

Was the first house in Southwark built after the Flood,

And has such a succession of vintners known,

Not more names were e'er in Welsh pedigrees shown:

But claret with them was so much out of fashion,

That it has not been known there a whole generation.”

The White Lion, formerly a prison for the county of Surrey, as well as an inn, is mentioned in records in the reign of King Henry VIII, having belonged to the Priory of St. Mary Overy. It is also mentioned by Stow, and it continued to be the county prison till 1695. The rabble apprentices of the year 1640, as Laud relates in his Troubles, released the whole of the prisoners in the White Lion. It has been supposed that the White Lion was the same house that, before the building of new London Bridge, was called Baxter's Chophouse, No. 19 High-street; and in old deeds, the Crown, or the Crown and Chequers: an old plasterfronted house. The house which stood in the court beside it, and was formerly called the Three Brushes, or “Holy Water Sprinklers,” was of the time of Elizabeth; and some drawings exist of the interior, as a panelled room, with an ornamental plaster ceiling, having in the centre the arms of Queen Elizabeth, with E. R., in support of the opinion that this room was the court or justice-room in which her Majesty's justices sat and held their sessions. This is more probable than that the house was a palace of Henry VIII, and that from thence he took a trip to Bermondsey Fair with Cardinal Wolsey, and there fell in love with Anna Bullen. The house was pulled down about 1832, for making the new street to London Bridge.

Mr. Corner was by no means certain that the White Lion was the same house as that used for the county prison; for at that time, when houses were not numbered, especially if they were occupied by tradesmen, they were known by signs; from which it did not follow that they were public-houses. But Stow distinctly states that there was in the High-street of Southwark an inn called the White Lion, which was used as a prison for the county of Surrey; and during the reign of Queen Elizabeth Roman Catholic recusants were confined here. Other Southwark inns named by Stow remain, except the Christopher; but they have mostly lost their galleries and their antique features. The King's Head was, within our recollection, a well-painted half-length of Henry VIII. The Catherine Wheel remains; but we miss the Dog and Bear, which sign, as well as Maypole-alley, hard by, points to olden sport and pas time.*