Taverns of Fleet street . - Henry C Shelley

Save for the High Street of Southwark, there was probably no thoroughfare of old

London which could boast so many inns and taverns to the square yard as Fleet

Street, but ere the pilgrim explores that famous neighbourhood he should visit

several other spots where notable hostelries were once to be seen. He should,

for example, turn his steps towards St. Paul's Churchyard, which, despite the

fact that it was chiefly inhabited by booksellers, had its Queen's Arms tavern

and its Goose and Gridiron.

Memories of David Garrick and Dr. Johnson are associated with the Queen's Arms.

This tavern was the meeting-place of a select club formed by a few intimate

friends of the actor for the express purpose of providing them with

opportunities to enjoy his society. Its members included James Clutterback, the

city merchant who gave Garrick invaluable financial aid when he started at Drury

Lane, and John Paterson, that helpful solicitor whom the actor selected as one

of his executors. These admirers of "little David" were a temperate set; "they

were 'none of them drinkers, and in order to make a reckoning called only for

French wine." Johnson's association with the house is recorded by Boswell as

belonging to the year 1781. "On Friday, April 6," he writes, "he carried me to

dine at a club which, at his desire, had been lately formed at the Queen's Arms

in St. Paul's Churchyard. He told Mr. Hoole that he wished to have a City

_Club_, and asked him to collect one; but, said he, 'Don't let them be

_patriots_.' The company were to-day very sensible, well-behaved men." Which,

taken in conjunction with the abstemious nature of the Garrick club, would seem

to show that the Queen's Arms was an exceedingly decorous house.

Concerning the Goose and Gridiron only a few scanty facts have survived. Prior

to the Great Fire it was known as the Mitre, but on its being rebuilt it was

called the Lyre. When it came into repute through the concerts of a favourite

musical society being given within its walls, the house was decorated with a

sign of Apollo's lyre, surmounted by a swan. This provided too good an

opportunity for the wits of the town to miss, and they promptly renamed the

house as the Goose and Gridiron, which recalls the facetious landlord who, on

gaining possession of premises once used as a music-house, chose for his sign a

goose stroking the bars of a gridiron and inscribed beneath, "The Swan and

Harp." It is an interesting note in the history of the St. Paul's Churchyard

house that early in the eighteenth century, on the revival of Freemasonry in

England, the Grand Lodge was established here.

Almost adjacent to St. Paul's, that is, in Queen's Head Passage, which leads

from Paternoster Row into Newgate Street, once stood the famous Dolly's Chop

House, the resort of Fielding, and Defoe, and Swift, and Dryden, and Pope and

many other sons of genius. It was built on the site of an ordinary owned by

Richard Tarleton, the Elizabethan actor whose playing was so humorous that it

even won the praise of Jonson. He was indeed such a merry soul, and so great a

favourite in clown's parts, that innkeepers frequently had his portrait painted

as a sign. The chief feature of the establishment which succeeded Tarleton's

tavern appears to have been the excellence of its beef-steaks. It should also be

added that they were served fresh from the grill, a fact which is accentuated by

the allusion which Smollett places in one of Melford's letters to Sir Walkin

Phillips in "Humphry Clinker": "I send you the history of this day, which has

been remarkably full of adventures; and you will own I give you them like a

beef-steak at Dolly's, _hot_ and_hot_, without ceremony and parade."

Out into Newgate Street the pilgrim should now make his way in search of that

Salutation Tavern which is precious for its associations with Coleridge and Lamb

and Southey. Once more, alas! the new has usurped the place of the old, but

there is some satisfaction in being able to gaze upon the lineal successor of so

noted a house. The Salutation was a favourite social resort in the eighteenth

century and was frequently the scene of the more formal dining occasions of the

booksellers and printers. There is a poetical invitation to one such function, a

booksellers' supper on January 19, 1736, which reads:

"You're desired on Monday next to meet

'At Salutation Tavern, Newgate Street,

Supper will be on table just at eight."

One of those rhyming invitations was sent to Samuel Richardson, the novelist,

who replied in kind:

"For me I'm much concerned I cannot meet

At Salutation Tavern, Newgate Street."

Another legend credits this with being the house whither Sir Christopher Wren

resorted to smoke his pipe while the new St. Paul's was being built. More

authentic, however, and indeed beyond dispute, are the records which link the

memories of Coleridge and Lamb and Southey with this tavern It was here Southey

found Coleridge in one of his many fits of depression, but pleasanter far are

the recollections which recall the frequent meetings of Lamb and Coleridge,

between whom there was so much in common. They would not forget that it was at

the nearby Christ's Hospital they were schoolboys together, the reminiscences of

which happy days coloured the thoughts of Elia as he penned that exquisite

portrait of his friend: "Come back into memory, like as thou wert in the

day-spring of thy fancies, with hope like a fiery column before thee--the dark

pillar not yet turned--Samuel Taylor Coleridge--Logician, Metaphysician,

Bard!--How have I seen the casual passer through the cloisters stand still,

entranced with admiration to hear thee unfold, in thy deep and sweet

intonations, the mysteries of Jamblichus, or Plotinus, or reciting Homer in his

Greek, or Pindar--while the walls of the old Grey Friars re-echoed to the

accents of the inspired charity-boy!" As Coleridge was the elder by two years he

left Christ's Hospital for Cambridge before Lamb had finished his course, but he

came back to London now and then, to meet his schoolmate in a smoky little room

of the Salutation and discuss metaphysics and poetry to the accompaniment of

egg-hot, Welsh rabbits, and tobacco. Those golden hours in the old tavern left

their impress deep in Lamb's sensitive nature, and when he came to dedicate his

works to Coleridge he hoped that some of the sonnets, carelessly regarded by the

general reader, would awaken in his friend "remembrances which I should be sorry

should be ever totally extinct--the 'memory 'of summer days and of delightful

years,' even so far back as those old suppers at our old Salutation Inn,--when

life was fresh and topics exhaustless--and you first kindled in me, if not the

power, yet the love of poetry and beauty and kindliness."

Continuing westward from Newgate Street, the explorer of the inns and taverns of

old London comes first to Holborn Viaduct, where there is nothing of note to

detain him, and then reaches Holborn proper, with its continuation as High

Holborn, which by the time of Henry III had become a main highway into the city

for the transit of wood and hides, corn and cheese, and other agricultural

products. It must be remembered also that many of the principal coaches had

their stopping-place in this thoroughfare, and that as a consequence the inns

were numerous and excellent and much frequented by country gentlemen on their

visits to town. Although those inns have long been swept away, the quaint

half-timbered buildings of Staple Inn remain to aid the imagination in

repicturing those far-off days when the Dagger, and the Red Lion, and the Bull

and Gate, and the Blue Boar, and countless other hostelries were dotted on

either side of the street.

With the first of these, the Dagger Tavern, we cross the tracks of Ben Jonson

once more. Twice does the dramatist allude to this house in "The Alchemist," and

the revelation that Dapper frequented the Dagger would have conveyed its own

moral to seventeenth century playgoers, for it was then notorious as a resort of

the lowest and most disreputable kind. The other reference makes mention of

"Dagger frumety," which is a reminder that this house, as was the case with

another of like name, prided itself upon the excellence of its pies, which were

decorated with a representation of a dagger. That these pasties were highly

appreciated is the only conclusion which can be drawn from the contemporary

exclamation, "I'll not take thy word for a Dagger pie," and from the fact that

in "The Devil is an Ass" Jonson makes Iniquity declare that the 'prentice boys

rob their masters and "spend it in pies at the Dagger and the Woolsack."

A second of these Holborn inns bore a sign which has puzzled antiquaries not a

little. The name was given as the Bull and Gate, but the actual sign was said to

depict the Boulogne Gate at Calais. Here, it is thought, a too phonetic

pronunciation of the French word led to the contradiction of name and sign. What

is more to the point, and of greater interest, is the connection Fielding

established between Tom Jones and the Bull and Gate. When that hero reached

London in his search after the Irish peer who brought Sophia to town, he entered

the great city by the highway which is now Gray's Inn Road, and at once began

his arduous search. But without success. He prosecuted his enquiry till the

clock struck eleven, and then Jones "at last yielded to the advice of Partridge,

and retreated to the Bull and Gate in Holborn, that being the inn where he had

first alighted, and where he retired to enjoy that kind of repose which usually

attends persons in his circumstances."

No less notable a character than Oliver Cromwell is linked in a dramatic manner

with the histories of the Blue Boar and the Red Lion inns. The narrative of the

first incident is put in Cromwell's own mouth by Lord Broghill, that

accomplished Irish peer whose conversion from royalism to the cause of the

Commonwealth was accomplished by the Ironsides general in the course of one

memorable interview. According to this authority, Cromwell once declared that

there was a time when he and his party would have settled their differences with

Charles I but for an incident which destroyed their confidence in that monarch.

What that incident was cannot be more vividly described than by the words Lord

Broghill attributed to Cromwell. "While we were busied in these thoughts," he

said, "there came a letter from one of our spies, who was of the king's

bed-chamber, which acquainted us, that on that day our final doom was decreed;

that he could not possibly tell us what it was, but we might find it out, if we

could intercept a letter, sent from the king to the queen, wherein he declared

what he would do. The letter, he said, was sewed up in the skirt of a saddle,

and the bearer of it would come with the saddle upon his head, about ten of the

clock that night, to the Blue Boar Inn in Holborn; for there he was to take

horse and go to Dover with it. This messenger knew nothing of the letter in the

saddle, but some persons at Dover did. We were at Windsor, when we received this

letter; and immediately upon the receipt of it, Ireton and I resolved to take

one trusty fellow with us, and with troopers' habits to go to the Inn in

Holborn; which accordingly we did, and set our man at the gate of the Inn, where

the wicket only was open to let people in and out. Our man was to give us

notice, when any one came with a saddle, whilst we in the disguise of common

troopers called for cans of beer, and continued drinking till about ten o'clock:

the sentinel at the gate then gave notice that the man with the saddle was come

in. Upon this we immediately arose, and, as the man was leading out his horse

saddled, came up to him with drawn swords and told him that we were to search

all that went in and out there; but as he looked like an honest man, we would

only search his saddle and so dismiss him. Upon that we ungirt the saddle and

carried it into the stall, where we had been drinking, and left the horseman

with our sentinel: then ripping up one of the skirts of the saddle, we there

found the letter of which we had been informed: and having got it into our own

hands, we delivered the saddle again to the man, telling him he was an honest

man, and bid him go about his business. The man, not knowing what had been done,

went away to Dover. As soon as we had the letter we opened it; in which we found

the king had acquainted the queen, that he was now courted by both the factions,

'the Scotch Presbyterians and the Army; and which bid fairest for him should

have him; but he thought he should close with the Scots, sooner than the other.

Upon this we took horse, and went to Windsor; and finding we were not likely to

have any tolerable terms with the king, we immediately from that time forward

resolved his ruin."

As that scene at the Blue Boar played so important a part in the sequence of

events which were to lead to Cromwell's attainment of supreme power in England,

so another Holborn inn, the Red Lion, was to witness the final act of that petty

revenge which marked the downfall of the Commonwealth. Perplexing mystery

surrounds the ultimate fate of Cromwell's body, but the record runs that his

corpse, and those of Ireton and Bradshaw, were ruthlessly torn from their graves

soon after the Restoration and were taken to the Red Lion, whence, on, the

following morning, they were dragged on a sledge to Tyburn and there treated

with the ignominy hitherto reserved for the vilest criminals. All kinds of

legends surround these gruesome proceedings. One tradition will have it that

some of Cromwell's faithful friends rescued his mutilated remains, and buried

them in a field on the north side of Holborn, a spot now covered by the public

garden in Red Lion Square. On the other hand grave doubts have been expressed as

to whether the body taken to the Red Lion was really that of Cromwell. One

legend asserts that it was not buried in Westminster Abbey but sunk in the

Thames; another that it was interred in Naseby field; and a third that it was

placed in the coffin of Charles I at Windsor.

Impatient though he may be to revel in the multifarious associations of Fleet

Street, the pilgrim should turn aside into Ludgate Hill for a few minutes for

the sake of that Belle Sauvage inn the name of which has been responsible for a

rich harvest of explanatory theory. Addison contributed to it in his own

humorous way. An early number of the Spectator was devoted to the discussion of

the advisability of an office being established for the regulation of signs, one

suggestion being that when the name of a shopkeeper or innkeeper lent itself to

"an ingenious sign-post" full advantage should be taken of the opportunity. In

this connection Addison offered the following explanation of the name of the

Ludgate Hill inn, which, it has been shrewdly conjectured by Henry B. Wheatley,

was probably intended as a joke. "As for the bell-savage, which is the sign of a

savage man standing by a bell, I was formerly very much puzzled upon the conceit

of it, till I accidentally fell into the reading of an old romance translated

out of the French; which gives an account of a very beautiful woman who was

found in a wilderness, and is called in the French La Belle Sauvage; and is

everywhere translated by our countrymen the bell-savage."

Not quite so poetic is the most feasible explanation of this unusual name for an

inn. It seems that the original sign of the house was the Bell, but that in the

middle of the fifteenth century it had an alternative designation. A deed of

that period speaks of "all that tenement or inn with its appurtenances, called

Savage's inn, otherwise called the Bell on the Hoop." This was evidently a case

where the name of the host counted for more than the actual sign of the house,

and the habit of speaking of Savage's Bell may easily have led to the perversion

into Bell Savage, and thence to the Frenchified form mostly used to-day.

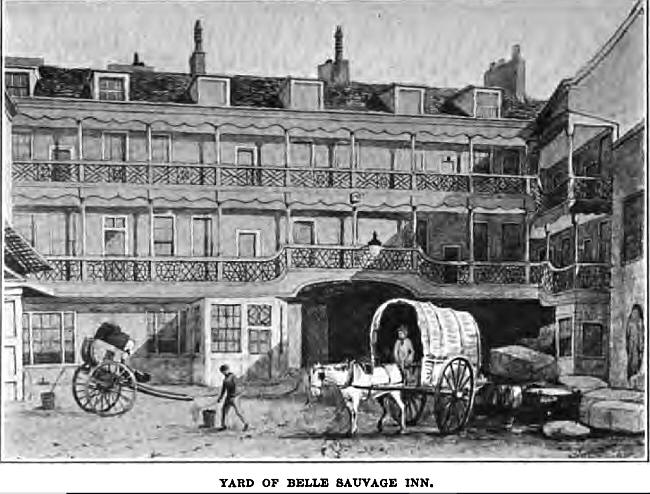

Leaving these questions of etymology for more certain matters, it is interesting

to recall that it was in the yard of the Belle Sauvage Sir Thomas Wyatt's

rebellion came to an inglorious end. That rising was ostensibly aimed at the

prevention of Queen Mary's marriage with a prince of Spain, and for that reason

won a large measure of support from the men of Kent, at whose head Wyatt marched

on the, capital. At London Bridge, however, his way was blocked, and he was

obliged to make a détour by way of Kingston, in the hope of entering the city by

Lud Gate. But his men became disorganized on the long march, and at each stage

more and more were cut off from the main body by the queen's forces, until, by

the time he reached Fleet Street, the rebel had only some three hundred

followers. "He passed Temple Bar," wrote Froude, "along Fleet Street, and

reached Ludgate. The gate was open as he approached, when some one seeing a

number of men coming up, exclaimed, 'These be Wyatt's ancients.' Muttered curses

were heard among the by-standers; but Lord Howard was on the spot; the gates,

notwithstanding the murmurs, were instantly closed; and when Wyatt knocked,

Howard's voice answered, 'Avaunt! traitor; thou shall not come in here.' 'I have

kept touch,' Wyatt exclaimed; but his enterprise was hopeless now, He sat down

upon a bench outside the Belle Sauvage yard." That was the end. His followers

scattered in all directions, and in a little while he was a prisoner, on his way

to the Tower and the block.

[Illustration: YARD OF BELLE SAUVAGE INN.]

More peaceful are the records which tell how the famous carver in wood, Grinling

Gibbons, and the notorious quack, Richard Rock, once had lodgings in the Belle

Sauvage Yard, and more picturesque are the memories of those days when the inn

was the starting-place of those coaches which lend a touch of romance to old

English life. Horace Walpole says Gibbons signalized his tenancy by carving a

pot of flowers over a doorway, so delicate in leaf and stem that the whole shook

with the motion of the carriages passing by. The quack, into the hands of whom

and his like Goldsmith declared all fell unless they were "blasted by lightning,

or struck dead with some sudden disorder," was a "great man, short of stature,

fat," and waddled as he walked. He was "usually drawn at the top of his own

bills, sitting in his arm-chair, holding a little bottle between his finger and

thumb, and surrounded with rotten teeth, nippers, pills, packets, and

gallipots."

From the Belle Sauvage to the commencement of Fleet Street is but a stone's

throw, but the pilgrim must not expect to find any memorials of the past in the

eastern portion of that famous thoroughfare. The buildings here are practically

all modern, many of them, indeed, having been erected in the last decade. As

these lines are being written, too, the announcement is made of a project for

the further transformation of the street at the cost of half a million pounds.

The idea is to continue the widening of the thoroughfare further west, and if

that plan is carried out, devastation must overtake most of the ancient

buildings which still remain.

By far the most outstanding feature of the Fleet Street of to-day is the number

and variety of its newspaper offices; two centuries ago it had a vastly

different aspect.

"From thence, along that tipling street,

Distinguish'd by the name of Fleet,

Where Tavern-Signs hang thicker far,

Than Trophies down at Westminster;

And ev'ry Bacchanalian Landlord

Displays his Ensign, or his Standard,

Bidding Defiance to each Brother,

As if at Wars with one another."

How thoroughly the highway deserved the name of "tipling street" may be inferred

from the fact that its list of taverns included but was not exhausted by the

Devil, the King's Head, the Horn, the Mitre, the Cock, the Bolt-in-Tun, the

Rainbow, the Cheshire Cheese, Hercules Pillars, the Castle, the Dolphin, the

Seven Stars, Dick's, Nando's, and Peele's. No one would recognize in the

Anderton's Hotel of to-day the lineal successor of one of these ancient taverns,

and yet it is a fact that that establishment perpetuates the Horn tavern of the

fifteenth century. In the early seventeenth century the house was in high favour

with the legal fraternity, but its patronage of the present time is of a more

miscellaneous character. The present building was erected in 1880.

[Illustration: THE CHESHIRE CHEESE--ENTRANCE FROM FLEET STREET.]

Close by, a low and narrow archway gives access to Wine Office Court, a spot

ever memorable for its having been for some three years the home of Oliver

Goldsmith. It was in 1760, when in his thirty-second year, that he took lodgings

in this cramped alleyway, and here he remained, toiling as a journeyman for an

astute publisher, until towards the end of 1762. So improved were Goldsmith's

fortunes in these days that he launched out into supper parties, one of which,

in May, 1761, was rendered memorable by the presence of Dr. Johnson, who attired

himself with unusual care for the occasion. To a companion who, noting the new

suit of clothes, the new wig nicely powdered, and all else in harmony, commented

on his appearance, Johnson rejoined, "Why, sir, I hear that Goldsmith, who is a

very great sloven, justifies his disregard of cleanliness and decency by quoting

my practice, and I am desirous this night to show him a better example." The

house where that supper party was held has disappeared, but in the Cheshire

Cheese nearby there yet survives a building which the centuries have spared.

Exactly how old this tavern is cannot be decided. It is inevitable that there

must have been a hostelry on this spot before the Great Fire of 1666, inasmuch

as there is a record to show that it was rebuilt the following year. Which goes

to show that the present building has attained the ripe age of nearly two and a

half centuries. No one who explores its various apartments will be likely to

question that fact. Everything about the place wears an air of antiquity, from

the quaint bar-room to the more private chambers upstairs. The chief glory of

the Cheshire Cheese, however, is to be seen downstairs on the left hand of the

principal entrance. This is the genuinely old-fashioned eating-room, with its

rude tables, its austere seats round the walls, its sawdust-sprinkled floor,

and, above all, its sacred nook in the further right hand corner which is

pointed out as the favourite seat of Dr. Johnson. Above this niche is a copy of

the Reynolds portrait of the sturdy lexicographer, beneath which is the

following inscription: "The Favourite Seat of Dr. Johnson.--Born 18th Septr.,

1709. Died 13th Decr., 1784. In him a noble understanding and a masterly

intellect were united with grand independence of character and unfailing

goodness of heart, which won him the admiration of his own age, and remain as

recommendations to the reverence of posterity. 'No, Sir! there is nothing which

has yet been contrived by man by which so much happiness has been produced as by

a good tavern.'"

[Illustration: THE CHESHIRE CHEESE--THE JOHNSON ROOM.]

After all this it is surprising to learn that the authority for connecting Dr.

Johnson with the Cheshire Cheese rests upon a somewhat late tradition. Boswell

does not mention the tavern, an omission which 'is accounted for by noting that

"Boswell's acquaintance with Johnson began when Johnson was an old man, and when

he had given up the house in Gough Square, and Goldsmith had long departed from

Wine Office Court. At the best," this apologist adds, "Boswell only knew

Johnson's life in widely separated sections." As appeal cannot, then, be made to

Boswell it is made to others. The most important of these witnesses is a Cyrus

Jay, who, in a book of reminiscences published in 1868, claimed to have

frequented the Cheshire Cheese for fifty-five years, and to have known a man who

had frequently seen Johnson and Goldsmith in the tavern. Another writer has

placed on record that he often met in the tavern gentlemen who had seen the

famous pair there on many occasions.

Taking into account these traditions and the further fact that the building

supplies its own evidence as to antiquity, it is not surprising that the

Cheshire Cheese enjoys an enviable popularity with all who find a special appeal

in the survivals of old London. As a natural consequence more recent writing in

prose and verse has been bestowed upon this tavern than any other of the

metropolis. Perhaps the best of the many poems penned in its praise is that

"Ballade" written by John Davidson, the poet whose mysterious disappearance has

added so sad a chapter to the history of literature.

"I know a house of antique ease

Within the smoky city's pale,

A spot wherein the spirit sees

Old London through a thinner veil.

The modern world so stiff and stale,

You leave behind you when you please,

For long clay pipes and great old ale

And beefsteaks in the 'Cheshire Cheese.'

"Beneath this board Burke's, Goldsmith's knees

Were often thrust--so runs the tale--

'Twas here the Doctor took his ease

And wielded speech that like a flail

Threshed out the golden truth. All hail,

Great souls! that met on nights like these

Till morning made the candles pale,

And revellers left the 'Cheshire Cheese.'

"By kindly sense and old decrees

Of England's use they set the sail

We press to never-furrowed seas,

For vision-worlds we breast the gale,

And still we seek and still we fail,

For still the 'glorious phantom' flees.

Ah well! no phantom are the ale

And beefsteaks of the 'Cheshire Cheese.'

"If doubts or debts thy soul assail,

If Fashion's forms its current freeze,

Try a long pipe, a glass of ale,

And supper at the 'Cheshire Cheese.'"

While the Cheshire Cheese was less fortunate than the Cock in the Fire of

London, the latter house, which escaped that conflagration, has fallen on

comparatively evil days in modern times. In other words, the exterior of the

original building, which dated from early in the seventeenth century, was

demolished in 1888, to make room for a branch establishment of the Bank of

England. Pepys knew the old house and spent many a jovial evening beneath its

roof. It was thither, one April evening in 1667, that he took Mrs. Pierce and

Mrs. Knapp, the latter being the actress whom he thought "pretty enough" besides

being "the most excellent, mad-humoured thing, and sings the noblest that ever I

heard in my life." The trio had a gay time; they "drank, and eat lobster, and

sang" and were "mightily merry." By and by the crafty diarist deleted Mrs.

Pierce from the party, and went off to Vauxhall with the fair actress, his

confidence in the enterprise being strengthened by the fact that the night was

"darkish." If she did not find out that excursion, Mrs. Pepys knew quite enough

of her husband's weakness for Mrs. Knapp to be justified of her jealousy. And

even he appears to have experienced twinges of conscience on the matter. Perhaps

that was the reason why he took his wife to the Cock, and "did give her a

dinner" there. Other sinners have found it comforting to exercise repentance on

the scene of their offences.

Judging from an advertisement which was published in 1665, the proprietor of the

Cock did not allow business to interfere with pleasure. "This is to certify,"

his announcement ran, "that the master of the Cock and Bottle, commonly called

the Cock Alehouse, at Temple Bar, hath dismissed his servants, and shut up his

house, for this Long Vacation, intending (God willing) to return at Michaelmas

next."

But the tavern is prouder of its association with Tennyson than of any other

fact in its history. The poet was always fond of this neighbourhood. His son

records that whenever he went to London with his father, the first item on their

programme was a walk in the Strand and Fleet Street. "Instead of the stuccoed

houses in the West End, this is the place where I should like to live," Tennyson

would say. During his early days he lodged in Norfolk Street close by, dining

with his friends at the Cock and other taverns, but always having a preference

for the room "high over roaring Temple-bar." In the estimation of the poet, as

his son has chronicled, "a perfect dinner was a beef-steak, a potato, a cut of

cheese, a pint of port, and afterwards a pipe (never a cigar). When joked with

by his friends about his liking for cold salt beef and new potatoes, he would

answer humorously, 'All fine-natured men know what is good to eat.' Very genial

evenings they were, with plenty of anecdote and wit."

All this, especially the pint of port, throws light on "Will Waterproof's

Lyrical Monologue," which, as the poet himself has stated, was "made at the

Cock." Its opening apostrophe is familiar enough:

"O plump head-waiter at The Cock,

To which I most resort,

How goes the time? 'Tis five o'clock.

Go fetch a pint of port."

How faithfully that waiter obeyed the poet's injunction to bring him of the

best, all readers of the poem are aware:

"The pint, you brought me, was the best

That ever came from pipe."

Undoubtedly. As witness the flights of fancy which it created. Its potent

vintage transformed both the waiter and the sign of the house in which he served

and shaped this pretty legend.

"And hence this halo lives about

The waiter's hands, that reach

To each his perfect pint of stout,

His proper chop to each.

He looks not like the common breed.

That with the napkin dally;

I think he came like Ganymede,

From some delightful valley.

"The Cock was of a larger egg

Than modern poultry drop,

Stept forward on a firmer leg,

And cramm'd a plumper crop;

Upon an ampler dunghill trod,

Crow'd lustier late and early,

Sipt wine from silver, praising God,

And raked in golden barley.

"A private life was all his joy,

Till in a court he saw

A something-pottle-bodied boy

That knuckled at the law:

He stoop'd and clutch'd him, fair and good,

Flew over roof and casement:

His brothers of the weather stood

Stock-still for sheer amazement.

"But he, by farmstead, thorpe and spire,

And follow'd with acclaims,

A sign to many a staring shire

Came crowing over Thames.

Right down by smoky Paul's they bore,

Till, where the street grows straiter,

One fix'd for ever at the door,

And one became head-waiter."

Just here the poet bethought himself. It was time to rein in his fancy. Truly it

was out of place to make

"The violet of a legend blow

Among the chops and steaks."

So he descends to more mundane things, to moralize at last upon the waiter's

fate and the folly of quarrelling with our lot in life. It is interesting to

learn from Fitzgerald that the Cock's plump head-waiter read the poem, but

disappointing to know that his only remark on the performance was, "Had Mr.

Tennyson dined oftener here, he would not have minded it so much." From which

poets may learn the moral that to trifle with Jove's cupbearer in the interests

of a tavern waiter is liable to lead to misunderstanding. But it is, perhaps, of

more importance to note that, notwithstanding the destruction of the exterior of

the Cock in 1888, one room of that ancient building was preserved intact and may

be found on the first floor of the new house. There, for use as well as

admiration, are the veritable mahogany boxes which Tennyson knew,--

"Old boxes, larded with the steam

Of thirty thousand dinners--"

and not less in evidence is the stately old fireplace which Pepys was familiar

with.

Not even a seat or a fireplace has survived of the Mitre tavern of Shakespeare's

days, or the Mitre tavern which Boswell mentions so often. They were not the

same house, as has sometimes been stated, and the Mitre of to-day is little more

than a name-successor to either. Ben Jonson's plays and other literature of the

seventeenth century make frequent mention of the old Mitre, and that was no

doubt the tavern Pepys patronized on occasion.

No one save an expert indexer would have the courage to commit himself to the

exact number of Boswell's references to the Mitre. He had a natural fondness for

the tavern as the scene of his first meal with Johnson, and with Johnson

himself, as his biographer has explained, the place was a first favourite for

many years. "I had learned," says Boswell in recording the early stages of his

acquaintance with his famous friend, "that his place of frequent resort was the

Mitre Tavern in Fleet Street, where he loved to sit up late, and I begged I

might be allowed to pass an evening with him there, which he promised I should.

A few days afterwards I met him near Temple-bar, about one o'clock in the

morning, and asked if he would then go to the Mitre. 'Sir,' said he, 'it is too

late; they won't let us in. But I'll go with you another night with all my

heart.'" That other night soon came. Boswell called for his friend at nine

o'clock, and the two were soon in the tavern. They had a good supper, and port

wine, but the occasion was more than food and drink to Boswell. "The orthodox

high-church sound of the Mitre,--the figure and manner of the celebrated Samuel

Johnson,--the extraordinary power and precision of his conversation, and the

pride arising from finding myself admitted as his companion, produced a variety

of sensations, and a pleasing elevation of mind beyond what I had ever before

experienced."

On the next occasion Goldsmith was of the company, and the visit after that was

brought about through Boswell's inability to keep his promise to entertain

Johnson at his own rooms. The little Scotsman had a squabble with his landlord,

and was obliged to take his guest to the Mitre. "There is nothing," Johnson

said, "in this mighty misfortune; nay, we shall be better at the Mitre." And

Boswell was characteristically oblivious of the slur on his gifts as a host. But

that, perhaps, is a trifle compared with the complacency with which he records

further snubbings administered to him at that tavern. For example, there was

that rainy night when Boswell made some feeble complaints about the weather,

qualifying them with the profound reflection that it was good for the vegetable

creation. "Yes, sir," Johnson rejoined, "it is good for vegetables, and for the

animals who eat those vegetables, and for the animals who eat those animals."

Then there was that other occasion when the note-taker talked airily about his

interview with Rousseau, and asked Johnson whether he thought him a bad man,

only to be crushed with Johnson's, "Sir, if you are talking jestingly of this, I

don't talk with you. If you mean to be serious, I think him one of the worst of

men." Severer still was the rebuke of another conversation at the Mitre. The

ever-blundering Boswell rated Foote for indulging his talent of ridicule at the

expense of his visitors, "making fools of his company," as he expressed it.

"Sir," Johnson said, "he does not make fools of his company; they whom he

exposes are fools already: he only brings them into action."

But, if only in gratitude for what Boswell accomplished, last impressions of the

Mitre should not be of those castigations. A far prettier picture is that which

we owe to the reminiscences of Dr. Maxwell, who, while assistant preacher at the

Temple, had many opportunities of enjoying Johnson's company. Dr. Maxwell

relates that one day when he was paying Johnson a visit, two young ladies, from

the country came to consult him on the subject of Methodism, to which they were

inclined. "Come," he said, "you pretty fools, dine with Maxwell and me at the

Mitre, and we will take over that subject." Away, they went, and after dinner

Johnson "took one of them upon his knee, and fondled her for half an hour

together." Dante Gabriel Rossetti chose that incident for a picture, but neither

his canvas nor Dr. Maxwell's record enlightens us as to whether the "pretty

fools" were preserved to the Church of England. But it was a happy

evening--especially for Dr. Johnson.

As with the Cock, a part of the interior of the Rainbow Tavern dates back more

than a couple of centuries. The chief interest of the Rainbow, however, lies in

the fact that it was at first a coffee-house, and one of the earliest in London.

It was opened in 1657 by a barber named James Farr who evidently anticipated

more profit in serving cups of the new beverage than in wielding his scissors

and razor. He succeeded so well that the adjacent tavern-keepers combined to get

his coffee-house suppressed, for, said they, the "evil smell" of the new drink

"greatly annoyed the neighbourhood." But Mr. Farr prospered in spite of his

competitors, and by and by he turned the Rainbow into a regular tavern.

No one who gazes upon the century-old print of the King's Head can do other than

regret the total disappearance of that picturesque building. This tavern stood

at the west corner of Chancery Lane and is believed by antiquaries to have been

built in the reign of Edward VI. It figures repeatedly in ancient engravings of

the royal processions of long-past centuries, and contributed a notable feature

to the progress of Queen Elizabeth as she was on her way to visit Sir Thomas

Gresham. The students of the Temple hit upon the effective device of having

several cherubs descend, as it were, from the heavens, for the purpose of

presenting the queen with a crown of gold and laurels, together with the

inevitable verses of an Elizabethan ceremony, and the roof of the King's Head

was chosen as the heaven from whence these visitants came down. Only the first

and second floors were devoted to tavern purposes; on the ground floor were

shops, from one of which the first edition of Izaak Walton's "Complete Angler"

was sold, while another provided accommodation for the grocery business of

Abraham Cowley's father.

From 1679 the King's Head was the common headquarters of the notorious Green

Ribbon Club, which included a precious set of scoundrels among its members,

chief of them all being that astounding perjurer, Titus Gates. Hence the

tavern's designation as a "Protestant house." It was pulled down in 1799.

Another immortal tavern of Fleet Street, the most immortal of them all, Ben

Jonson's Devil, has also utterly vanished. Its full title was The Devil and St.

Dunstan, aptly represented by the sign depicting the saint holding the tempter

by the nose, and its site, appropriately enough, was opposite St. Dunstan's

Church, on the south side of Fleet Street and close to Temple-bar. One of

Hogarth's illustrations to "Hudibras" gives a glimpse of the tavern, but on the

wrong side of the street, as is so common in the work of that artist.

No doubt the Devil had had a protracted existence prior to Jonson's day, but its

chief title to fame dates from the time when the convivial dramatist made it his

principal rendezvous. The exact date of that event is difficult to determine.

Nor is it possible to explain why Jonson removed his patronage from the Mermaid

in Cheapside to the Devil in Fleet Street. The fact remains, however, that while

the earlier period of his life has its focus in Cheapside the later is centred

in the vicinity of Temple-bar.

[Illustration: TABLET AND BUST FROM THE DEVIL TAVERN.]

Perhaps Jonson may have found the accommodation of the Devil more suited to his

needs. After passing through those years of opposition which all great poets

have to face, there came to him the crown of acknowledged leadership among the

writers of his day. He accepted it willingly. He seems to have been

temperamentally fitted to the post. He was, in fact, never so happy as when in

the midst of a group of men who owned his pre-eminence. What was more natural,

then, than that he should have conceived the idea of forming a club? And in the

great Apollo room at the Devil he found the most suitable place of meeting. Over

the door of this room, inscribed in gold letters on a black ground, this

poetical greeting was displayed.

"Welcome all who lead or follow

To the Oracle of Apollo--

Here he speaks out of his pottle,

Or the tripos, his tower bottle:

All his answers are divine,

Truth itself doth Bow in wine.

Hang up all the poor hop-drinkers,

Cries old Sam, the king of skinkers;

He the half of life abuses,

That sits watering with the Muses.

Those dull girls no good can mean us;

Wine it is the milk of Venus,

And the poet's horse accounted:

Ply it, and you all are mounted.

'Tis the true Phoebian liquor,

Cheers the brains, makes wit the quicker.

Pays all debts, cures all diseases,

And at once three senses pleases.

Welcome all who lead or follow,

To the Oracle of Apollo."

That relic of the Devil still exists, carefully preserved in the banking

establishment which occupies the site of the tavern; and with it, just as

zealously guarded, is a bust of Jonson which stood above the verses. Inside the

Apollo room was another poetical inscription, said to have been engraved in

black marble. These verses were in the dramatist's best Latin, and set forth the

rules for his tavern academy. Much of their point is lost in the English

version, which, however, deserves quotation for the sake of the inferences it

suggests as to the conduct which was esteemed "good form" in Jonson's club.

"As the fund of our pleasure, let each pay his shot,

Except some chance friend, whom a member brings in.

Far hence be the sad, the lewd fop, and the sot;

For such have the plagues of good company been.

"Let the learned and witty, the jovial and gay,

The generous and honest, compose our free state;

And the more to exalt our delight whilst we stay,

Let none be debarred from his choice female mate.

"Let no scent offensive the chamber infest.

Let fancy, not cost, prepare all our dishes.

Let the caterer mind the taste of each guest,

And the cook, in his dressing, comply with their wishes.

"Let's have no disturbance about taking places,

To show your nice breeding, or out of vain pride.

Let the drawers be ready with wine and fresh glasses,

Let the waiters have eyes, though their tongues must be ty'd.

"Let our wines without mixture or stum, be all fine,

Or call up the master, and break his dull noddle.

Let no sober bigot here think it a sin,

To push on the chirping and moderate bottle.

"Let the contests be rather of books than of wine,

Let the company be neither noisy nor mute.

Let none of things serious, much less of divine,

When belly and head's full profanely dispute.

"Let no saucy fidler presume to intrude,

Unless he is sent for to vary our bliss.

With mirth, wit, and dancing, and singing conclude,

To regale every sense, with delight in excess.

"Let raillery be without malice or heat.

Dull poems to read let none privilege take.

Let no poetaster command or intreat

Another extempore verses to make.

"Let argument bear no unmusical sound,

Nor jars interpose, sacred friendship to grieve.

For generous lovers let a corner be found,

Where they in soft sighs may their passions relieve.

"Like the old Lapithites, with the goblets to fight,

Our own 'mongst offences unpardoned will rank,

Or breaking of windows, or glasses, for spight,

And spoiling the goods for a rakehelly prank.

"Whoever shall publish what's said, or what's done,

Be he banished for ever our assembly divine.

Let the freedom we take be perverted by none

To make any guilty by drinking good wine."

By the testimony of those rules alone it is easy to see how thoroughly the

masterful spirit of Jonson ruled in the Apollo room. His air was a throne, his

word a sceptre that must be obeyed. This impression is confirmed by many records

and especially by Drummond's character sketch. The natural consequence was that

membership in the Apollo Club came to be regarded as an unusual honour. There

appears to have been some kind of ceremony at the initiation of each new member,

which gave all the greater importance to the rite of being "sealed of the tribe

of Ben." Long after the dramatist was dead, his "sons" boasted of their intimacy

with him, much to the irritation of Dryden and others. While he lived, too, they

were equally elated at being admitted to the inner circle at the Devil, and,

after the manner of Marmion, sung the praises of their "boon Delphic god,"

surrounded with his "incense and his altars smoking."

Incense was an essential if Jonson was to be kept in good humour. Many anecdotes

testify to that fact. There is the story of his loss of patience with the

country gentleman who was somewhat talkative about his lands, and his

interruption, "What signifies to us your dirt and your clods? Where you have an

acre of land, I have ten acres of wit." And Howell tells of that supper party

which, despite good company, excellent cheer and choice wines, was turned into a

failure by Jonson engrossing all the conversation and "vapouring extremely of

himself and vilifying others." Yet there were probably few of his own circle,

the "sons of Ben," who would have had it otherwise. Few indeed and fragmentary

are the records of his conversation in the Apollo room, but they are sufficient

to prove how ready a wit the poet possessed. Take, for example, the story of

that convivial gathering when the tavern keeper promised to forgive Jonson the

reckoning if he could tell what would please God, please the devil, please the

company, and please him. The poet at once replied:

"God is pleased, when we depart from sin,

The devil's pleas'd, when we persist therein;

Your company's pleas'd, when you draw good wine,

And thou'd be pleas'd, if I would pay thee thine."

Some austere biographers have chided the memory of the poet for spending so much

of his time at the Devil. They forget, or are ignorant of the fact that there is

proof the time was well spent. In a manuscript of Jonson which still exists

there are many entries which go to show that some of his finest work was

inspired by the merry gatherings in the Apollo room.

For many years after Jonson's death the Devil, and especially the Apollo room,

continued in high favour with the wits of London and the men about town. Pepys

knew the house, of course, and so did Evelyn, and Swift dined there, and Steele,

and many another genius of the eighteenth century. It was in the Apollo room,

too, that the official court-day odes of the Poets Laureate were rehearsed,

which explains the point of the following lines:

"When Laureates make odes, do you ask of what sort?

Do you ask if they're good or are evil?

You may judge--From the Devil they come to the Court,

And go from the court to the Devil."

But the Apollo room is not without its idyllic memory. It was created by the

ever-delightful pen of Steele. Who can forget the picture he draws of his sister

Jenny and her lover Tranquillus and their wedding morning? "The wedding," he

writes, "was wholly under my care. After the ceremony at church, I resolved to

entertain the company with a dinner suitable to the occasion, and pitched upon

the Apollo, at the Old Devil at Temple-bar, as a place sacred to mirth tempered

with discretion, where Ben Jonson and his sons used to make their liberal

meetings." The mirth of that assembly was threatened by the indiscretion of that

double-meaning speaker who is usually in evidence at such gatherings to the

confusion of the bride, but happily his career was cut short by the plain sense

of the soldier and sailor, as may be read in the pages of the "Tatler."

Within easy hail of the Devil, on the site now occupied by St. Clement's

Chambers, Dane's Inn, there stood until 1853 a quaint old hostelry known as the

Angel Inn. It dated from the opening years of the sixteenth century at least,

for it is specifically named in a letter of February 6th, 1503. In the middle of

that century, too, it figures in the progress of Bishop Harper to the martyr's

stake, for it was from this inn that prelate was taken to Gloucester to be

burnt. The Angel cannot hope to compete with the neighbouring taverns of Fleet

Street on the score of literary associations, but the fact that seven or eight

mail coaches started from its yard every night will indicate how large a part it

played in the life of old London.